Covid-19 variants and genomic surveillance

Image credit: Dan Ross / Wellcome Sanger Institute

Covid variants arise when mutations in SARS-CoV-2 virus affect how infectious or deadly it is. Genomic surveillance helps track new variants and their impact.

What is a Covid-19 variant?

- Genomic surveillance sequences the genetic material of pathogens, allowing us to identify and track new variants of a pathogen such as SARS-CoV-2, and so helping us control the spread of diseases like Covid-19.

- The genetic material of SARS-CoV-2 – like the genetic material of all organisms - has the ability to change or mutate. These mutations may be small, with little or no effect on the characteristics of the virus, or large with big consequences.

- When the genetic material of a pathogen mutates in a way which affects either how quickly and easily the virus infects cells or how lethal the infection is, they are considered sufficiently different for it to be called a variant.

- Variants are identified by genomic sequencing. The RNA bases from SARS-CoV-2 viruses found in samples from many infected people are sequenced and compared. Differences in the genomes are linked to differences in the behaviour or shape of the virus to see if they are important to human health.

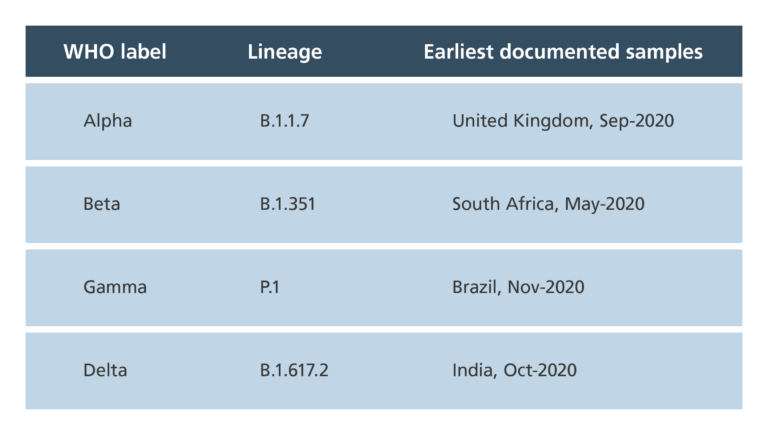

- Variants have been alternatively named after where they were first detected (UK/Kent variant, South Africa variant…), their scientific names (B.1.1.7, P1…) and now the Greek alphabet (Alpha, Delta…).

- If a variant appears that is sufficiently different from other variants to make our immunity from previous infections or vaccines ineffective, it is called an escape variant. Essentially it has ‘escaped’ from our existing protections.

- Scientists are constantly on the alert for any variants that show a new characteristic – for example, the Delta variant that emerged in the early summer of 2021 and was much more infectious than earlier variants of the virus.

- Picking up potentially problematic variants is where genomic surveillance comes into its own. Scientists identify different types of variants:

- variants of concern (VOC), where there is clear evidence that the virus is passed on more easily, causes more severe disease or avoids the immune system

- variants of interest (VOI) where there is a possibility that the variant is more easily spread or more dangerous

- variants under monitoring, where surveillance identifies a new variant but there is not yet evidence to suggest it will cause problems

How has genomic surveillance helped with Covid-19 variants?

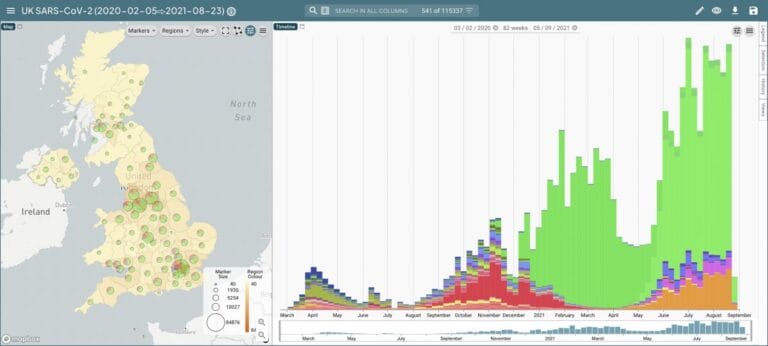

- Genomic surveillance is the use of sequencing to monitor whether the genetic sequence of an infectious agent is changing. This results in the discovery of new variants, and allows scientists to see if they are becoming more dominant in a particular area.

- When a new variant is thought to be spreading in an area, an increased testing regiment like surge testing can be implemented to track both the spread and characteristics of the variant.

- This testing is part of genomic surveillance when it is combined with sequencing and using bioinformatics to identify patterns in the data collected. Genomic surveillance is a powerful tool – never more so than when it is used in a disease outbreak such as Covid-19, ebola or MRSA.

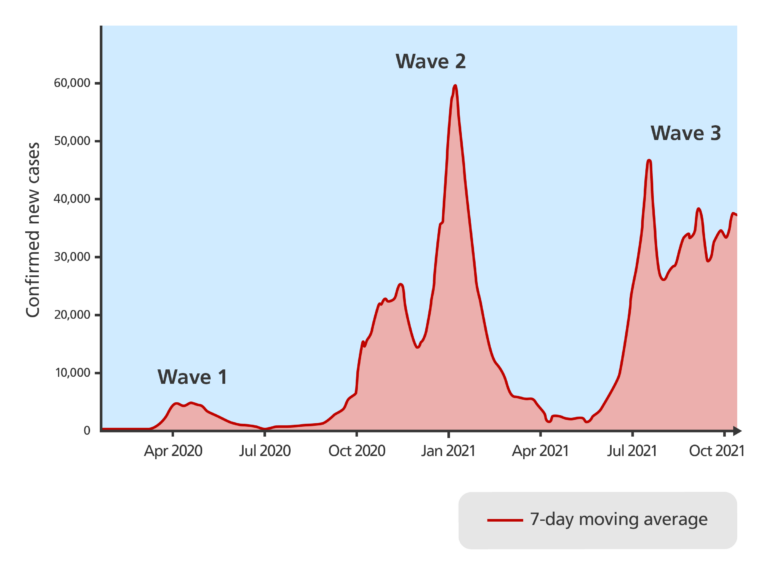

- In a pandemic such as covid-19, genomic surveillance data is very useful for scientists advising policy-makers, helping provide the evidence base for decisions on restrictions or determining if there will be new waves of infection.

- A wave is a resurgence of a virus through a population after it has died down for a while. Many pandemics have several, distinct waves. If scientists can identify new variants of the virus and they can be controlled before they cause a new wave of infections, then many lives may be saved.

Article written by Valerie Vancollie, Scientist and Product Lead for the COVID-19 Genomic Surveillance team at the Wellcome Sanger Institute.