How are stem cells used in research and medicine?

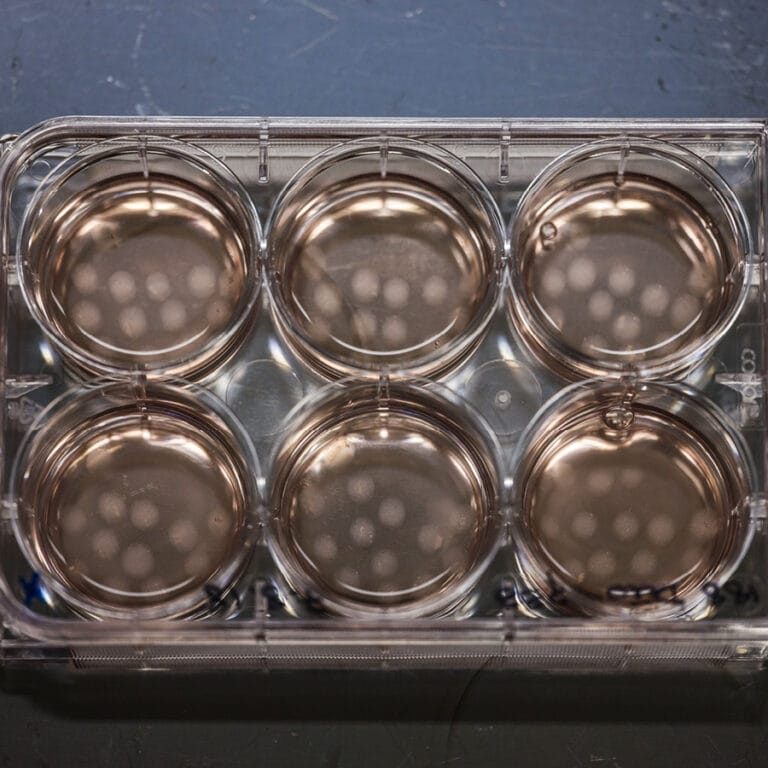

Greg Moss / Wellcome Sanger Institute

Stem cells can provide valuable information about early human development and why different diseases occur and could lead to new therapies to replace lost or damaged cells.

Key terms

Pluripotent

A cell with the ability to develop into any kind of specialised cell in the body.

Multipotent

A stem cell with the ability to develop into specific kinds of specialised cells, but not all cells in the body.

- A stem cell has the unique ability to develop into other specialised cell types in the body.

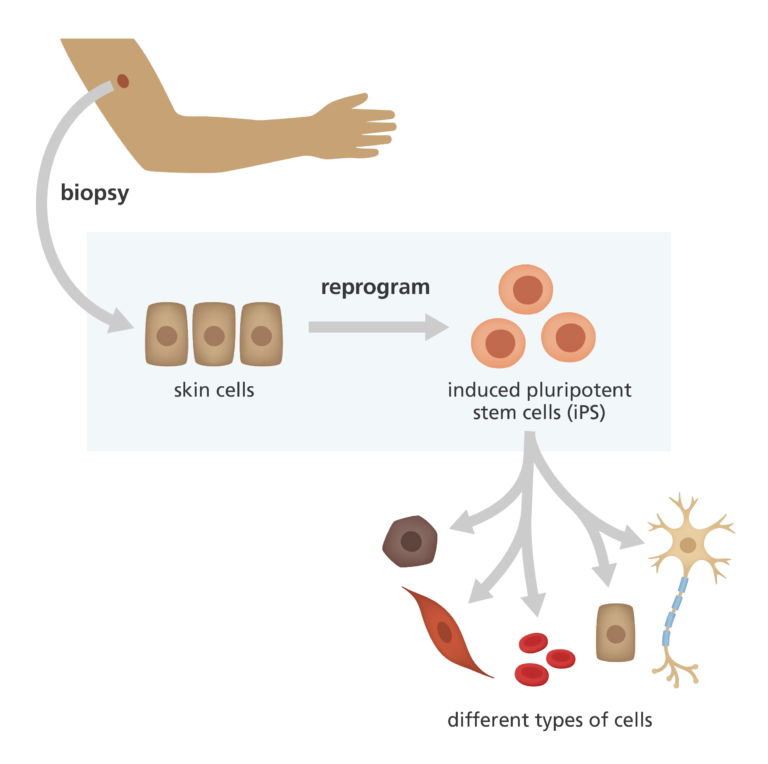

- Normal adult cells can be reprogrammed in the lab to become a stem cell – known as an induced pluripotent stem cell.

- Stem cells can be used in research to help us understand biology. They are also starting to be used in medicine to replace lost or damaged cells that the body isn’t able to replace naturally.

Induced pluripotent stem cells (or iPS cells)

- Stem cells are tightly controlled by a network of signals which turn on certain genes and turn off other genes. Some signals will keep cells in a stem cell state and other signals make them develop into a specialised cell – like a blood cell or a bone cell.

- Normal adult cells (often skin or blood cells) can be reprogrammed in the lab to become pluripotent stem cells. This is called ‘inducing’ the stem cell state.

- To generate induced pluripotent stem cells, scientists re-introduce the signals that normally tell stem cells to stay as stem cells in the early embryo.

- These signals switch off any genes that tell the cell to be specialised, and switch on genes that tell the cell to be a stem cell.

Using stem cells in research

- By growing and studying induced pluripotent stem cells in the lab, we can better understand how human bodies grow and develop.

- This includes exploring what happens to cells during the development of diseases, such as cancer or dementia.

- We can also grow tissue and organ structures from stem cells and use them to test new drugs for their safety and effectiveness.

- Stem cells can be sourced in a few ways and, sometimes, embryonic stem cells are used in research. This is carried out only with permission from the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority and can only take place on embryos up to 14 days old.

Using stem cells in medicine (stem cell therapy)

- Some people’s cells, tissues and organs can be permanently damaged or lost by disease, injury or genetic conditions.

- Stem cells – or stem cell therapy – may be able to generate new cells, which are transplanted into the body to create those that are damaged or lost.

- Adult stem cells are currently used in bone marrow transplants. This provides a source of blood cells for people with some blood conditions, such as thalassaemia, or people who have lost their own blood stem cells during treatments like chemotherapy for cancer.

The future of stem cell therapy

Clinical trials are currently underway to test new stem cell therapies. In the future, they could be used to treat different conditions by creating new cells, tissues and organs. For example:

Generating new skin

- for people with severe burns or wounds.

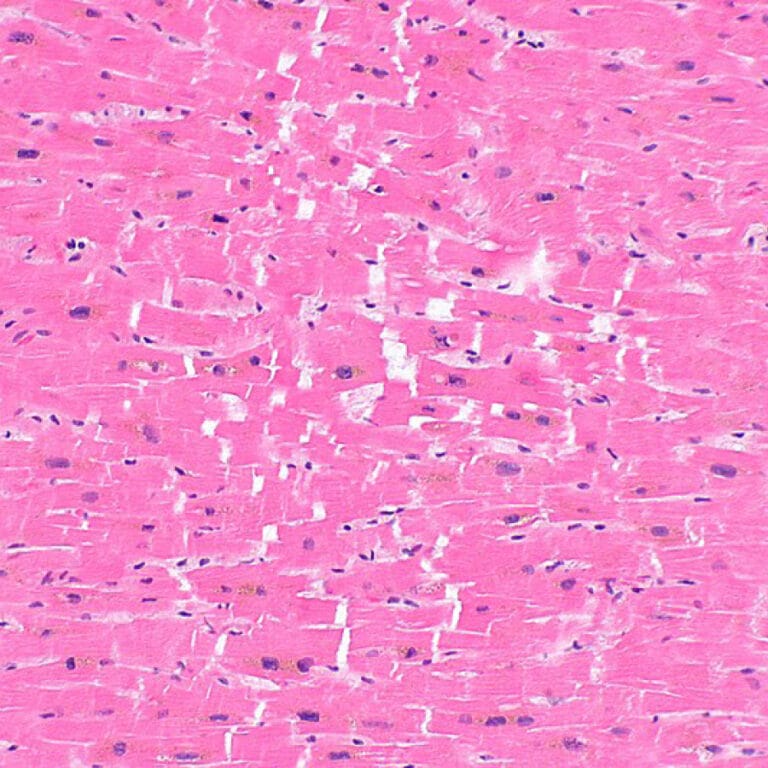

Replacing heart tissue

- in people with damage caused by heart failure or heart disease.

Creating new organs for use in transplants

- which might be safer than organs donated by another person – which have a risk of being rejected by the immune system.

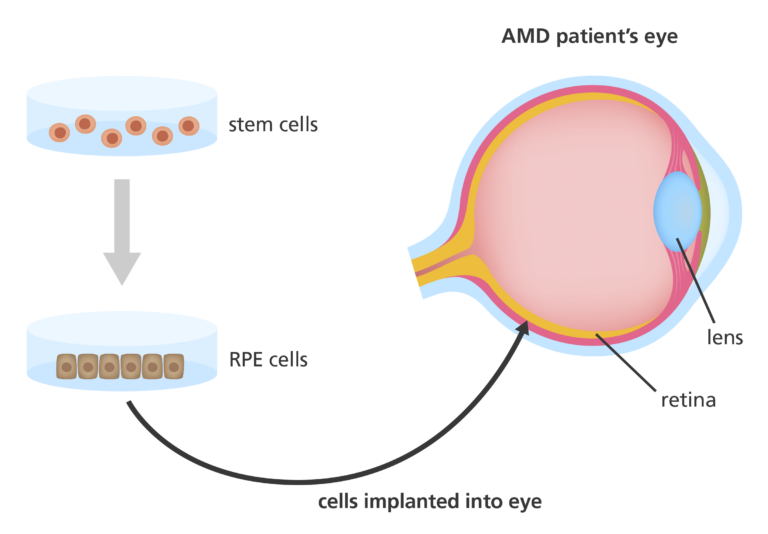

Replacing damaged eye cells

- in people with age-related macular generation (AMD), where the eye cells that produce retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) stop working, leading to blindness.