How is genomics being used to tackle leishmania?

By Emily Farthing, Freelancer writer and editor.

Leishmaniasis is a neglected tropical disease caused by protozoan parasites called Leishmanias, which are transmitted to humans by the bite of infected sandflies.

This is part 3 in our series looking at how genomics is being used to tackle neglected tropical diseases. You might want to read part 1 first, here.

- The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies 20 conditions as a ‘neglected tropical disease’, including leprosy, African sleeping sickness and rabies.

- Leishmania is one of these diseases. It’s caused by a protozoa parasite, which is transmitted by the bite of infected phlebotomine sandflies.

- The condition is most common in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. It affects some of the world’s poorest people, and is associated with malnutrition, population displacement, poor housing, a weak immune system and lack of financial resources.

- Around 30,000 people die from Leishmaniasis each year.

Key terms

Parasite

An organism that lives in or on another organism (the host) and benefits at the expense of their host.

What is leishmaniasis?

Leishmaniasis is a neglected tropical disease that has recently begun receiving interest from the genomics research community.

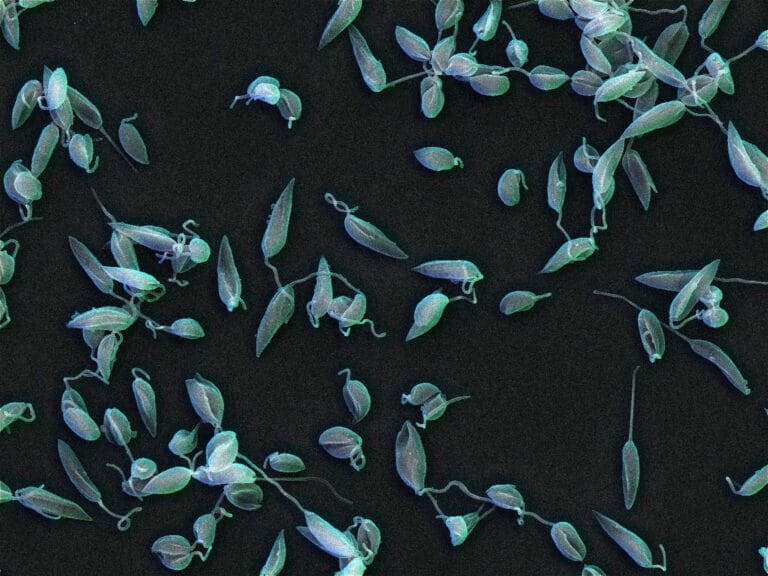

The disease is mostly found in tropical and subtropical regions, caused by protozoan parasites called Leishmanias, which are transmitted to humans by the bite of infected sandflies. More than 30 Leishmania parasites can infect humans, although only a small number of people who are infected will develop the disease leishmaniasis.

Generally, the control of leishmaniasis relies on early diagnosis, controlling the sandfly vector and managing of other animal hosts.

There are three main forms of leishmaniasis, each associated with different species of the Leishmania parasite:

- Visceral: the most serious and potentially fatal form of the disease. There are between 50,000 and 90,000 new cases of this form each year.

- Cutaneous: the most common form, which causes skin lesions such as ulcers. There are between 600,000 and 1 million new cases each year.

- Mucocutaneous: the form which can lead to partial or total destruction of the mucous membranes of the nose, mouth and throat. Exact numbers for this form are unknown.

The most studied type is visceral leishmaniasis, which can be fatal in around 95% of cases if it is left untreated. It’s caused by the parasite species Leishmania donovani.

The first entire genome sequence of the Leishmania major parasite was completed in 2005. Since then, several other Leishmania species have also been sequenced, including L infantum, L braziliensis, L mexicana and L donovani.

Having these genome sequences available has enabled scientists to advance their understanding of the parasites’ complex biology and the interactions between the parasites, host and vector, the sandfly.

Asexual vs sexual reproduction

Scientists have found that Leishmania parasite species seem to differ depending on which part of the world they are found. This is because the parasite is able to vary the way it reproduces.

In some areas, Leishmania parasites reproduce in a similar way to bacteria – by way of clonal expansion. This means that all the new generations or ‘daughter’ cells arise originally from a single cell. As a result, these populations of Leishmania grow and grow from a limited genetic pool – and are almost exact copies of each other.

By contrast, in other parts of the globe, the parasites reproduce sexually, exchanging chunks of DNA. This results in Leishmania parasites with a lot of genetic variation, gradually drifting apart into more varied and more distinct organisms.

The concern with this scenario is that different parasites could eventually be transmitted by vectors other than the sandfly. If Leishmania species are starting to mix it could result in the emergence of a more deadly parasite transmitted by an unexpected or, as yet unidentified, vector.

Understanding the ways that these parasites reproduce could lead to new ways to prevent its transmission.

Leishmaniasis in dogs

Dogs are the main animal hosts of Leishmania. Transmission of some Leishmania species relies on circulation of the parasite in canine populations.

Some gaps still exist in our understanding of the similarities and differences between human leishmaniasis and the disease that occurs in dogs. Knowing more about these similarities and differences could reveal if Leishmania has an ‘Achilles’ heel’ that scientists can target to help break the transmission cycle.

The main push with research into all neglected tropical diseases is, primarily, to find ways to prevent them, rather than just focusing on treatments. With genomics, scientists may be able to pinpoint the changes that are occurring during reproduction and transmission of these parasites. This may then enable them to develop effective treatments and control strategies against this devastating group of diseases.