Unsung heroes in science: Henrietta Lacks

Although not a scientist, Henrietta Lacks has been instrumental in biological research as her cancer cells became the first successful line of human cells to be grown in the lab. Her story has also prompted many ethical and moral questions about how scientific research is conducted.

Key terms

Cell

The basic structural and functional biological unit of all living things.

Cancer

A common genetic disease caused by mutations in DNA, and characterised by uncontrolled cell growth.

Henrietta Lacks was not a scientist – but the contribution that she has made to science has made a huge impact.

The first successful line of human cells grown in a lab came from a cancer sample taken from Henrietta. These cells have been used millions of times in countless labs across the world and have had an invaluable contribution towards scientific discovery. Henrietta’s story has also prompted many ethical and moral questions about how scientific work is conducted, about the rights and uses of cells and tissue taken from patients and about the treatment of African Americans and other marginalised communities in scientific and medical research.

Henrietta’s life

Henrietta was born in 1920 in Virginia, US. She spent her early life helping on her family’s tobacco farm before moving to Baltimore, Maryland, with her husband, shipyard worker David ‘Day’ Lacks. Henrietta and Day had five children.

In early 1951, Henrietta went to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore due to several worrying symptoms, including feeling a ‘knot’ in her stomach and having spots of blood in her underwear. Tests revealed that she had advanced cervical cancer. Despite several rounds of treatment, Henrietta died at Johns Hopkins Hospital on 4 October 1951, aged 31.

Sadly, not much is known about what Henrietta was like, and there are very few photographs of her.

Henrietta’s immortal cells

Henrietta’s contribution to science came about when some of her cells were taken by staff at Johns Hopkins hospital. These cells were then taken to the lab of George Gey, who had been trying to work out if it was possible to grow human cells in a lab. Up until this point, George and his team hadn’t been able to keep cells alive for more than a few days.

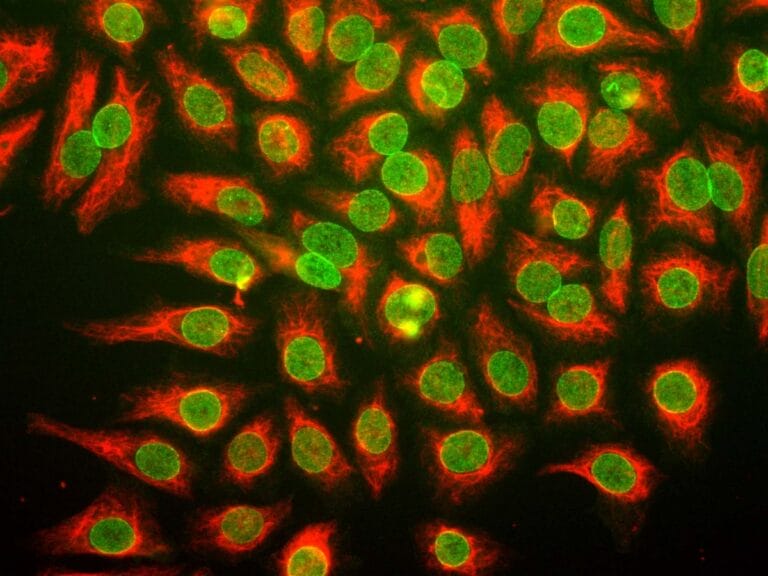

To their surprise, Henrietta’s cancer cells could successfully divide and replicate themselves in the laboratory. In fact, they just kept on dividing and growing – essentially becoming ‘immortal’. The cells were designated ‘HeLa’, after Henrietta Lacks. These immortal cells allowed for longer term, more complicated experiments to be performed and represented a huge leap forward in our ability to understand how human cells work.

George excitedly shared the cells with his colleagues, who then shared them with their colleagues. Eventually the cells were put into mass production and shared around the world. Since then, HeLa cells have contributed to many scientific breakthroughs, for example the development of the first polio vaccine.

In fact, HeLa cells are still used in scientific experiments to this day.

The cell line grown from Henrietta Lacks’ cancer sampler were designated ‘HeLa’

Ethical and moral considerations

The establishment of the HeLa cell line has raised a number of moral and ethical issues surrounding the use of human tissue in research.

Importantly, Henrietta’s cells were taken without her or her family’s knowledge or permission. It wasn’t until 1975, 24 years later, that the family found out a part of Henrietta was still ‘alive’ and being used in research. The discovery came because HeLa cells had been contaminating other cell lines and the family were contacted by researchers asking for blood samples to help identify which cells were HeLa cells.

Secondly, the family have raised concerns about what HeLa cells mean for their privacy – the full HeLa cell genome sequence was published without the permission of the Lacks family. In 2013, the HeLa Genome Data Use Agreement between the US National Institute of Health (NIH) saw two representatives of the Lacks family join a newly formed working group to review any new research proposal seeking access to the full HeLa genome sequence data.

Another issue is ownership. Scientists and companies own several patents that use HeLa cells, meaning they own and profit from these cells – but Henrietta and her family do not. Several different lines of lab-grown cells have since been grown from other patients’ tissues, and have been the subject of a number of court cases investigating who actually owns the cells.

In 1990, a ruling by the Supreme Court of California stated that cells used for scientific research are not the property of the patient and so the patient and their family have no right to any profits. However, in 2021, the Lacks family sued biotechnology company Thermo Fisher Scientific for “reaping billions of dollars from a racist medical system” and profiting from the unconsented collection and use of Henrietta’s cells. In 2023, more than 70 years after Henrietta’s death, the family and the company reached a settlement.

The establishment of the HeLa cell line has raised a number of moral and ethical issues surrounding the use of human tissue in research.

Medical inequities

Henrietta’s story has also prompted discussions about the way that Black people and others from marginalised communities have been treated by the medical and scientific fields.

The reason that Henrietta had to go to Johns Hopkins and be treated on a public ward was because no other hospital in the area would treat Black patients. The question about whether her cells were removed without her consent because she was Black is more controversial, with some arguing that this was a standard practice at the time, regardless of the patients’ race.

These are also questions about how researchers were able to access her cells without her permission in the first place, as it is doubtful that this practice of taking cells would have happened in the same way in a private hospital.

Recognising Henrietta Lacks

In recent years, much more recognition has been given to the contribution that Henrietta, her cells and her family have made to science over the past 70 years. The bestselling book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot, delves deeper into the story and brings Henrietta and her family more into the light. Buildings have been named after her, statues have been erected (including one in Bristol, UK) and charitable foundations have been created in her honour.

The HeLa cell line remains immortal and still continues to give researchers vital information and knowledge about how cells work.