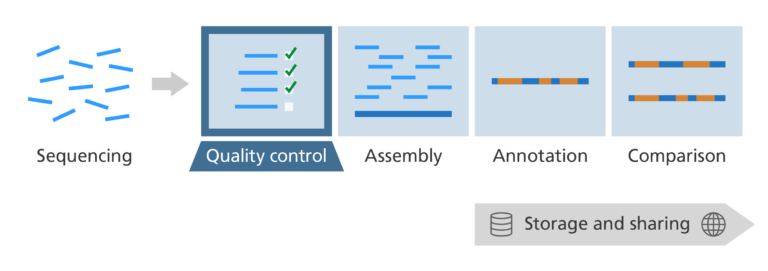

Post-sequencing: quality control

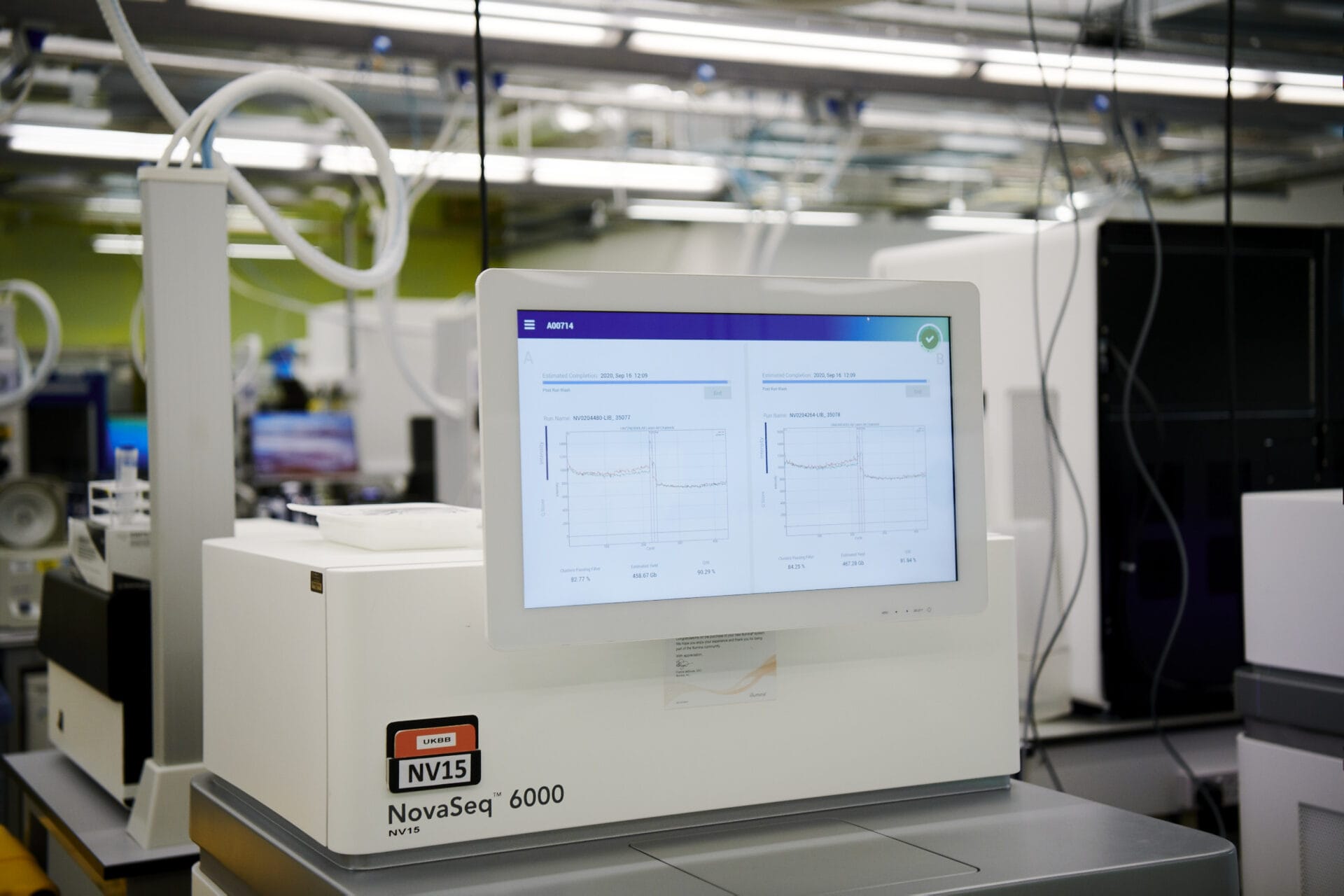

Image credit: Dan Ross / Wellcome Sanger Institute

What happens to DNA sequence when it comes off a sequencing machine? Step 1 is quality control.

This is part 1 in our series looking at what happens after DNA is sequenced.

- DNA sequencing produces huge amounts of data essentially comprising lots of short sections of DNA letters.

- The first step is to check that the sequence is of the highest quality before we start to piece the sections together.

- This first step is our quality control step.

What do we need to do when DNA comes off the sequencing machine?

After we have sequenced a sample of DNA, we need a quality control process to check that:

- The laboratory stage of the process, which prepares the DNA sample for sequencing, has worked properly.

- The instrument carrying out the sequencing itself has run properly.

- The DNA sample is from a single source and not contaminated with DNA from another sample.

What do we need to do?

Quality control is an extensive set of procedures carried out to ensure that the sample and DNA sequence are of good quality.

The DNA must be of suitable quality so that it can be sent on and used for scientific study.

- One way this is assessed is by looking at how much DNA (measured in clusters) are in every mm2 of each lane of the sequencing machine.

- For a sample to be accepted, there should be hundreds of thousands to millions of DNA clusters per mm2 of each lane (depending on the sequencing machine being used).

- If the number of clusters is outside the range for a certain machine it indicates that something has gone wrong during sequencing and the sample will not be accepted for further processing.

- The strength of the signal from the DNA bases in the sequence is also measured. The signal should be as bright as possible, particularly for the first base in the sequence. If the signal is dull, it means that something might have gone wrong or that the camera on the machine was out of focus.

The DNA sample can’t be contaminated with DNA from another sample.

- This is checked by aligning the DNA sequence against the reference genome for that organism and checking that it matches with the species it should be. For example, if you have sequenced a mouse genome you would expect to see a 98-99% match to the reference mouse genome and much lower matches with other reference genomes. It will never be 100 per cent because there is always some genetic variation between individuals of the same species.

- Individual ‘tags’ are added to each DNA sample before sequencing. These tags are short sequences of DNA that act as barcodes to identify DNA fragments from the same individual. These can then all be easily identified and sorted afterwards. After sequencing, if a tag does not appear in a sample when it should it is a sign that something has gone wrong before or during sequencing. This may be a result of contamination or human error.

- The time taken to transfer the sequence data off the machines and then undergo primary analysis takes about three to four days to complete. Although, the manual quality control process usually only takes about one hour.

- After this the sample will then either be passed or failed.

- If the sample is failed, the failed sequence will be discarded, and sequencing will be carried out again.

- For all the samples that pass, the DNA sequence is stored in a large data ‘bucket’ along with additional information about the sample. This will include which sample the DNA sequence is from, which species it is from, and which study the genome was sequenced for.