What is African sleeping sickness?

Image credit: By Zephyris - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10769382

African Trypanosomiasis is a parasitic disease transmitted by the tsetse fly. It’s dubbed ‘sleeping sickness’ because symptoms can include a disturbed sleep pattern.

- Trypanosomiasis is a group of diseases caused by Trypanosoma parasites, spread by fly bites.

- There are two main types divided by geographical region: African trypanosomiasis and American trypanosomiasis.

- Around 10,000 new cases of African trypanosomiasis are reported each year, across sub-Saharan Africa. However, it is estimated that many cases go undiagnosed.

- Trypanosomiasis is curable if treatment is given quickly. If left untreated, the disease can be fatal.

What is trypanosomiasis or African sleeping sickness?

- Trypanosomiasis refers to a group of diseases caused by Trypanosoma parasites.

- There are two types of trypanosomiasis that affect humans, divided according to their geographical location:

- African trypanosomiasis, or African sleeping sickness, is caused by Trypanosoma brucei parasites in sub-Saharan Africa and is transmitted by the tsetse fly.

- American trypanosomiasis, or Chagas disease, is caused by Trypanosoma cruzi parasites in Latin America and is transmitted by the triatomine or ‘kissing’ bug.

- Trypanosomiasis can affect all vertebrate animals, including cattle, wide game and domestic animals. Non-human animals tend to get a form called Nagana disease and can act as a host for human trypanosome parasites.

- While wild animals are mostly tolerant to the disease, for domestic animals, the infection can be severe and sometimes fatal.

What causes African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) in humans?

- African trypanosomiasis is caused by two subspecies of parasitic Trypanosoma brucei: Trypanosoma brucei gambiense (West African) and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (East African).

- Trypanosoma brucei gambiense is responsible for more than 98 per cent of all reported cases of human African trypanosomiasis and causes long-term, chronic infection.

- Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense is responsible for the remaining 2% of all reported cases of and causes acute infections that develop rapidly over a few weeks.

- Another subspecies, Trypanosome brucei brucei, does not affect humans.

How is African trypanosomiasis transmitted?

- Both subspecies of Trypanosoma are transmitted between humans via the bite of the tsetse fly, which is only found in rural parts of Africa.

- Communities most at risk of trypanosomiasis live in rural areas where the tsetse fly is found. These communities often depend primarily on agriculture, fishing and hunting to survive and have limited access to health services and education. As a result, many people with trypanosomiasis go undiagnosed and consequently do not receive the treatment they need.

- The Trypanosoma parasites can also be transmitted during pregnancy, as the parasite can cross the placenta and infect the baby while it is still in the womb.

- Contaminated needles can also contribute to the spread of Trypanosoma parasites, but this is rare.

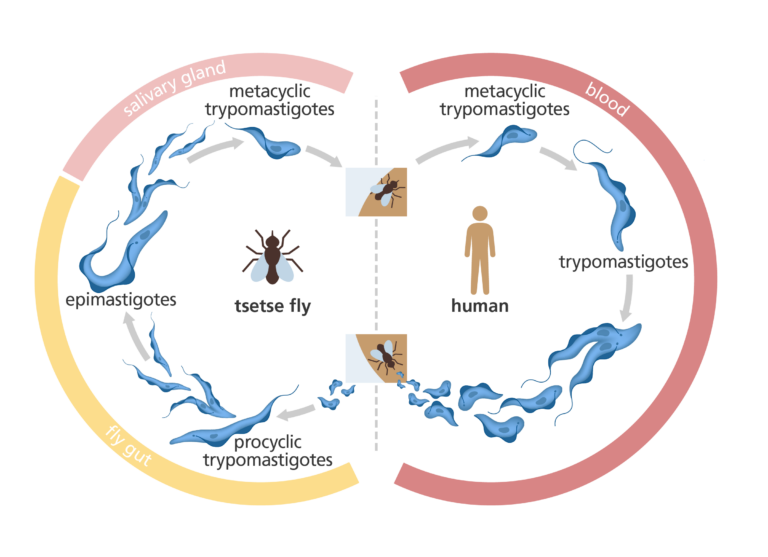

The Trypanosoma parasite life cycle

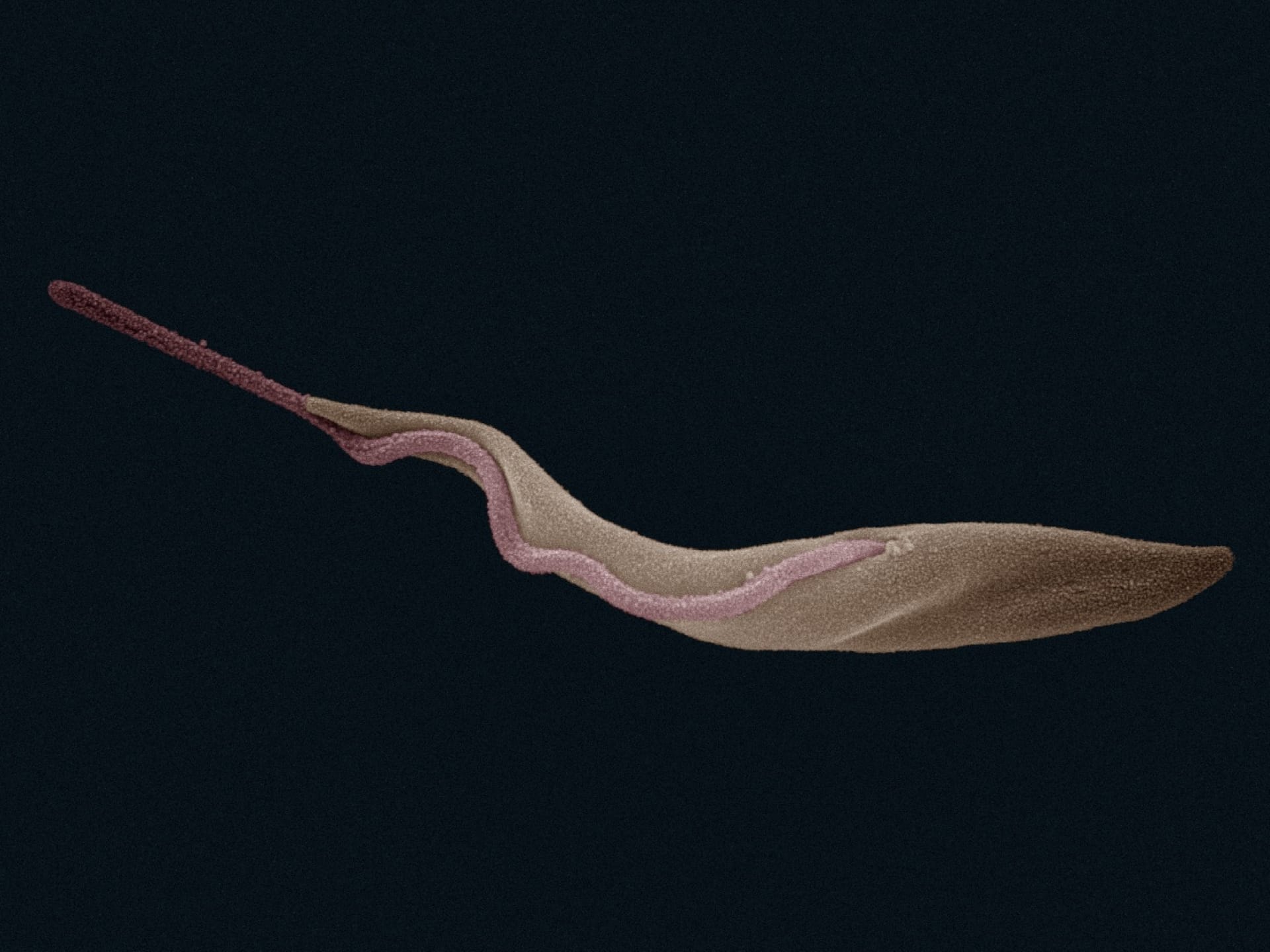

- The Trypanosoma parasite begins its life cycle in the tsetse fly, where it is in a short, stumpy form with a short flagellum (or tail).

- Once in the gut of the tsetse fly, the parasite multiplies and grows. They then move to the front of the gut, on the way to the fly’s salivary gland, where they attach themselves by their flagella.

- The parasite is first introduced into the human (or animal) host when the tsetse fly takes a blood meal and secretes parasite-filled saliva into the host’s skin.

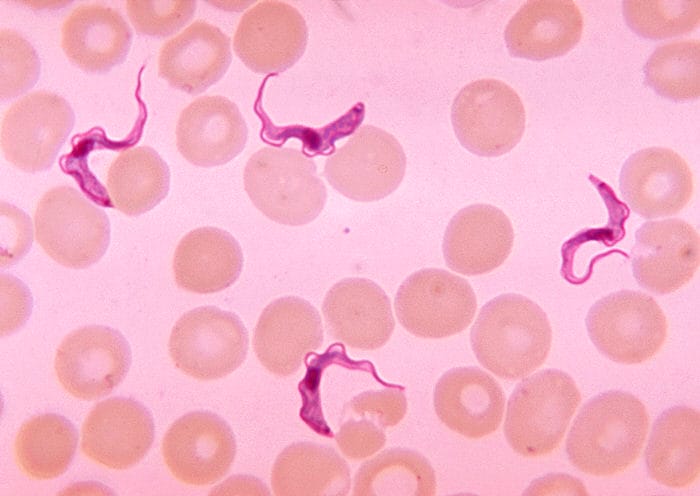

- Once in the human bloodstream, the parasites become longer and slenderer and develop longer flagellum, before spreading rapidly to other areas of the body. They then multiply in the blood, lymph or spinal fluid.

What are the symptoms of African trypanosomiasis?

- The symptoms of African trypanosomiasis are divided into two key stages:

- First stage or haemolymphatic phase: shortly after the parasites enter the body and multiply, an inflammatory reaction occurs. This causes swelling of the skin and enlargement of the lymph nodes in the neck. This immune response causes symptoms such as fever, headaches, joint pains and itching.

- Second stage or neurological phase: this stage begins when the parasites cross from the blood-brain barrier into the spinal fluid, infecting the central nervous system including the brain. Once the brain is affected it results in changes in behaviour, confusion, poor coordination, difficulties with speech and disturbance of sleep (sleeping through the day and insomnia at night), hence the term ‘sleeping sickness’.

- Without treatment, African trypanosomiasis can be fatal.

How is African trypanosomiasis screened for and diagnosed?

- African trypanosomiasis must be diagnosed as early as possible to prevent the disease from progressing into the second stage.

- Screening programmes have been established for some at-risk populations, involving:

- Checking for clinical signs, such as swollen lymph nodes in the neck and neurological signs such as an altered mental state or extended daytime sleeping.

- Examining blood smears for signs of the parasite.

- If screening tests are inconclusive, individuals may have a blood test looking for specific antibodies that signify the parasite is present.

- Further assessments then find out which stage the disease has progressed to.

- This involves taking a sample of spinal fluid via a lumbar puncture and looking for parasites. If parasites are present this indicates that the disease has progressed to the neurological phase.

- Screening of at-risk populations is a major investment, both in terms of the number of people needed to do them and the materials required.

- However, screening and on-going surveillance have been proven to effectively control the spread of the infection, as many people infected with trypanosomiasis are undiagnosed so do not receive treatment, increasing the overall spread.

- In areas without screening or where screening is relaxed, levels of the disease continue to increase.

How is trypanosomiasis treated?

- Trypanosomiasis is curable if treatment is given quickly, however if left untreated the disease is fatal.

- The type of treatment given depends on the stage of the disease and the subspecies of the parasite that caused it.

- Generally, the earlier the disease is identified, the easier it is to treat – the first stage can usually be treated with easy-to-administer drugs, with milder side effects.

- However, treatment is more aggressive once in the second stage of the disease, with more toxic drugs needed to kill the parasite after it has crossed the blood-brain barrier. These drugs are also more complicated to administer, usually requiring several weeks of drugs being given directly into the veins.

- As of 2023, six drugs are registered for treating African trypanosomiasis and are administered free of charge to countries where the disease is a problem. These include:

- Pentamidine: for first stage Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, it generally has no adverse side effects.

- Fexinidazole: for first stage and non-severe second stage Trypanosoma brucei gambiense.

- Suramin: for first stage Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, it causes some side effects such as urinary tract infections and allergic reactions.

Melarsoprol: for second stage Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense. It is derived from arsenic and has many unwanted side effects including, in some extreme cases, fatal reactive encephalopathy. There has also been a spread of resistance to melarsoprol in trypanosomes found in central Africa. - Eflornithine: for second stage Trypanosoma brucei gambiense. Originally developed as an anti-cancer drug, it is less toxic than melarsoprol but can cause vomiting, diarrhoea and anaemia.

Nifurtimox: for second stage Trypanosoma brucei gambiense. It is usually combined with eflornithine.

How can trypanosomiasis be prevented?

- There is currently no vaccine or preventative drug to help protect against African trypanosomiasis in people. However, the development of a vaccine is currently being researched and in 2021, a promising vaccine was shown to be effective at preventing the infection in cattle.

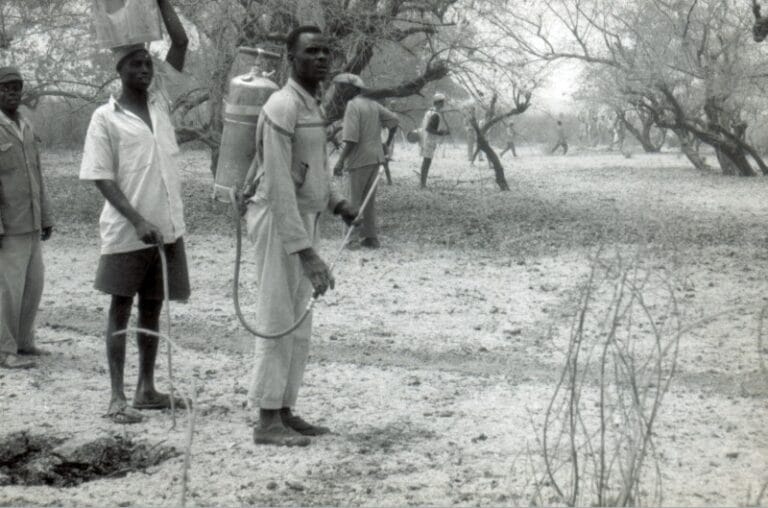

- Prevention is generally aimed at minimising contact with the tsetse fly, including:

- wearing long-sleeved shirts and long trousers to limit the amount of exposed skin.

- wearing clothes in neutral colours as tsetse flies are attracted to bright colours.

- avoiding bushes where the tsetse fly rest during the hottest part of the day as they will bite if disturbed.

- using strong insect repellent, using insecticides to kill the insect and deploying traps and screens in homes to reduce the flies entering.